Few youthful visitors to Tampa’s new Julian B. Lane Riverfront Park know about the ghosts. They head for the basketball courts, or toss a football on the lawn, or munch a Cuban sandwich in the picnic area. Sometimes you will see them kayaking in the Hillsborough or admiring the spectacular sculptures, mosaics and paintings scattered about the 25-acre park. Understandable.

You have to be special, like George Lopez, to be aware of the ghosts. You have to have white hair or walk with a cane. George was 89 when we first met. His best friend, Joe Doreo, was 90 when we shook hands. George and Joe, who met in first grade, told me their ghost story.

Left, Joe Doria, 90-right, George Lopez, 89 by Jeff Klinkenberg 2018

They told me that the $37-million park, named after a former mayor, rested upon the very ground where they had grown up. In 1893 it was called Ellinger City. And when the Ellinger City Cigar Factory closed, it was named after the new cigar factory that J. W. Roberts opened in 1909.

Roberts City, where George and Joe claimed their earliest memories, stretched 11 blocks long and only three blocks wide. It was bounded on two ends by the meandering Hillsborough River, and by Cass Street and North Boulevard elsewhere.

When most of Florida was segregated by race and ethnicity, working-class Roberts City was home to hundreds of families of Italians, Cubans, African Americans, Bahamians and Caucasians who lived as neighbors. Roberts City boasted groceries, bakeries, pharmacies, a linen factory, churches, a street car, seafood markets, and a fleet of commercial fishing boats. It had a hotel, boxing and, eventually, a football stadium. It was home to the only hospital available to African Americans for miles.

Roberts City residents included a giant of Florida’s civil rights movement – more about Robert Saunders Sr. later -- as well as ordinary folks who kept the world turning, folks who loved, sweated, danced, sang, got into mischief, and made something of themselves. Norman Rockwell might have enjoyed painting in Roberts City. It was Melting Pot America.

Yet Roberts City was pretty much gone by 1960. What happened was a changing world, modernity, and opportunities elsewhere. When factories shut their doors, residents left. When residents left, small businesses failed. The interstate cut through the fading neighborhood. Bulldozers demolished abandoned buildings.

Within decades Robert City was mostly forgotten by everybody but a few old timers like George Lopez, Joe Doreo and aging friends. The Roberts City boys, as they called themselves, gathered every Friday morning for coffee and memories. Not in Roberts City, because no coffee shops remained in the rubble. They gathered at El Gallo de Oro Restaurant miles away -- twenty or so elderly folks reminiscing in English, Italian or Spanish over café con leches.

Death never takes a day off. As the clock ticked, the Roberts City Boys fell in number. By the time I wrote this in 2018, I could find only two regulars. George and Joe were keeping Roberts City alive by telling stories of their old neighborhood.

“You remember the time?” George would start a tale with a chuckle. And Joe would finish it for him with a big laugh. Yes, that kid – no names, please – cheated at marbles.

Ghosts.

Yes, George Lopez and Joe Dorea believed in them. They could shut their eyes and see the long-gone faces of friends and family. They could smell the cigar smoke and the bread baking. They could hear music drifting off the front porches into the neighborhood that was no more.

“SUPPER!” their mothers would call, Joe’s in Italian and George’s in Spanish, and they would sprint in bare feet across the open yards

in the dying light.

Ghosts.

George Lopez, who didn’t go to college, was sometimes known as the “Roberts City historian” even without a diploma on his wall. That’s because he had never stopped collecting photographs and asking questions and paying attention to old stories. Over the years he donated gobs of pictures, notes and even handmade maps to the Special Collections Library at the University of South Florida. George supported his family by removing asbestos from buildings and as a hotel bellhop. But at night he wrote down his memories.

The Tampa Bay History Center, in fact, has sold his excellent book, I Am Your Father’s Brother, for years. It’s a warts-and-all biography of his family and friends and life in the lost neighborhood.

“Have you ever heard of Roberts City?’’ was the question George often asked a new acquaintance. He was usually disappointed at the reply. I fancied myself a pretty good Tampa Bay historian – go ahead, ask me something about Ybor City – but I failed George’s Roberts City test too.

In our many meetings he was always soft-spoken and polite. But his good manners couldn’t mask his determination to spread the word about his old community. For years he had called on folks at city hall and at history museums to ask if they knew about Roberts City. He resisted saying “tsk, tsk” at their answers. He bent the ear of the kindly Tampa Tribune history columnist, Leland Hawes, who understood George as a kindred spirit.

As time passed, George was able to raise funds for a plaque that would tell the Roberts City story. They put their historic marker on North Boulevard in front of the Boys and Girls Club.

A plaque is small thing, but maybe it would be a start.

In 2014, George was gratified to hear about the City of Tampa’s plan for a new riverfront park in the lost neighborhood. At last, he hoped, Roberts City would be remembered. Among other things the park was going to commission artists – more about them later – who would honor old icons in their work.

The city asked Tampa residents for their ideas. They wanted basketball courts and dog parks and running paths and picnic tables and maybe a football field and perhaps a place to launch kayaks. But they were interested in history too.

African Americans, for example, brought up the name of the late bakery owner, Fortune Taylor. A former slave, she had amassed – to this day nobody is quite sure how -- 33 acres on the bank of the Hillsborough near Roberts City. A black land owner was unusual enough back in the day, but no more so than a black woman who owned her own business. The 91-year-old bridge that connects the old Roberts City site to downtown Tampa is named after her.

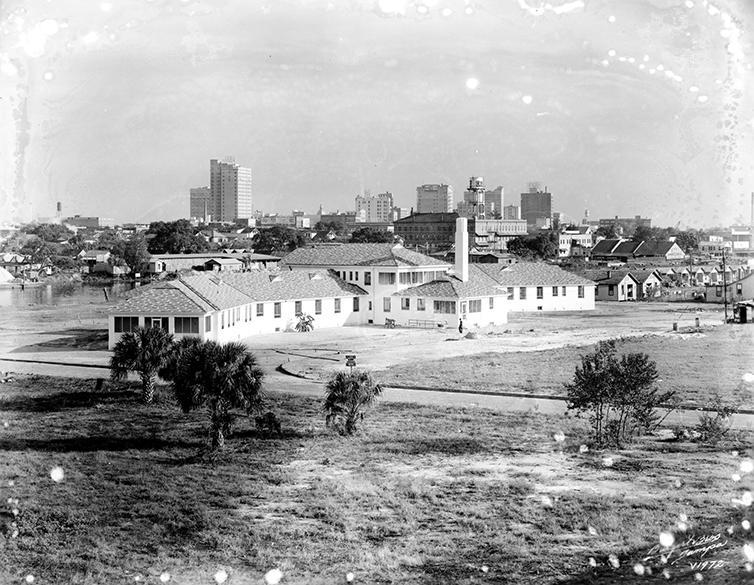

Clara Frye Hospital, Photo by University of South Florida Special Collections

Nobody wanted Clara C. Frye forgotten either. While blacks, whites, Italians and Cubans often were neighbors, skin color still mattered. African Americans suffering from malaria or TB often had nowhere to go. Frye welcomed patients of all races into her home and nursed them back to health. Later she founded a hospital in Roberts City, which stood at the site of today’s Tampa Blake High School. When segregation ended, and blacks were finally admitted to other hospitals, the aging Frye facility was deemed unnecessary. The ninth floor at Tampa General bears her name today.

Robert Saunders Sr., meanwhile, became a Florida civil-rights legend. Born in Tampa in 1921, he lived in Roberts City near his social-justice minded Bahamian-born grandparents. Among other things, they happened to be founding members of Tampa’s NAACP. As a child Saunders played with children of other races in the relatively accepting neighborhood. He ate at their homes and they ate at his. Still, in segregated Florida, he couldn’t attend white schools or churches because of the color of his skin.

African Americans who walked across the Fortune Taylor Bridge from Roberts City into downtown Tampa were subject to other humiliations. They were forbidden to sit at a dime-store lunch counter or use a rest room intended for white people. They were expected to ride in the back of the bus and avoid “white only” water fountains. A black mother and child entered the doctor’s office through the back door so intolerant white patients in the waiting room wouldn’t be upset. If that same mom wanted to buy her child new shoes, she had to hope she had remembered to trace her kid’s foot on a piece of paper. In Tampa’s department stores, white customers might refuse to buy a shoe, or even try on a shoe, if it had first been on the foot of a black person. Mom would hand over the tracing so the salesman could provide the properly sized footwear.

In 1938, Joe Louis fought Max Schmeling in New York’s Yankee Stadium in front of 70,000 fans. Schmeling, a German, whom the Nazis used for propaganda purposes, had knocked out the “Bronx Bomber” two years before. In the rematch, Louis knocked out Schmeling in the first round. In Roberts City, black residents staged an impromptu parade to celebrate their pride.

Robert Saunders Sr., who grew up in that complicated world, took notice of the good and the bad. After graduating from Florida’s Bethune-Cookman College and taking classes at the University of Detroit’s College of Law, he joined the NAACP in New York. Colleagues included Medgar Evers, later murdered in Mississippi by white supremacists for organizing black voters.

Robert Saunders, Photo by Hillsborough County Public Library

He might have remained in the more tolerant New York forever if it hadn’t been for a Florida tragedy. In 1951, somebody with hate in his heart detonated a bomb under a modest house in Central Florida, killing NAACP field secretary Harry T. Moore and his wife Harriet. Nobody was brought to justice for the killing.

With murder in the air, and the Ku Klux Klan lurking about, Saunders agreed to become Florida’s next NAACP field secretary. He registered black voters, worked to desegregate schools, protested police brutality, fought discrimination, and watched his back. Years later, the former child of Roberts City shook hands in the White House with President John F. Kennedy. He also served as Hillsborough County’s equal opportunity administrator. His year 2000 autobiography, Bridging the Gap, is still in print, though Saunders died as the result of an auto accident in 2002.

He joins Clara C. Frye and Fortune Taylor as Roberts City ghosts.

One day in 2018, when the bulldozers were still rumbling at Julian B. Lane Riverfront Park, I pulled on a hard hat and took a long walk into the past as imagined by the artists hired by the City of Tampa.

I saw spectacular monoliths that glittered like sparklers and featured whirligigs on top that reminded me of leaping mullet. Pilings, they were supposed to be – pilings that might have supported a ramshackle Roberts City seafood dock in a fairy tale. They had been created by North Carolina artist Thomas Sayre after a long look at the river.

A mysterious edifice near the river caught my eye. A tower for bats? More than a tower, Tampa artist Lynn Manos’s creation was more like a grand hotel -- complete with luminescent walls that changed color depending upon the light. For generations harmless Mexican free-tailed bats and evening bats roosted in the crevices of Hillsborough River bridges. Now they would have a chance to roost in luxury.

Next I admired a colorful mosaic created by Jovi Schnell of Los Angeles. An internationally known artist who spent her teenage years in Sarasota, Schnell had also chosen to celebrate the Roberts City seafood traditions in whimsical work on a building wall. It included everyday Hillsborough River underwater denizens as well as the mythical Afro-Cuban mermaid “Yemaya,” known to protect brave mariners.

Schnell’s bench tiles and inlays reflected other lost Roberts City traditions -- dominoes played by generations of Cubans and the game of bocce enjoyed by old-time Italians. Modern visitors, by the way, will have the opportunity to play dominoes and bocce nearby and think about the ghosts.

Roberts City historic marker; Background: Jovi Schnell's mosaic

I traipsed down the world’s grandest sidewalk, what Schnell called a “promenade,” paved with colorful pavers inspired by old-time cigar labels that once had wrapped Roberts City smokes. I have never smoked a cigar, but I if I ever do, I will sit on one of the tiled benches and admire the impressive art through the cloud of pungent smoke.

One afternoon I visited the airplane-hanger of a studio where artists known as the Pep Rally hung their respective ball caps. Jay Giroux and his crew -- and their partner Edgar Sanchez Cumbas -- were working on the 19-foot painting now found in the park’s River Center. In a series of original earth-toned paintings they told the story of Roberts City. Looking out from the painting were images of Phillips Field, cigar factories, seafood shacks, and the faces of prominent African Americans The painting captured the Roberts City that George Lopez long had worried would be forgotten.

His dad, Julian Antonio Lopez, was born in Cuba, migrated to Key West, and moved to Roberts City to labor in a cigar factory. Many cigars rollers were illiterate, so they hired an educated man to read to them as they toiled. The lector, as he was called, read them the Tampa Tribune, union tracts, and classic literature like Don Quixote.

George’s dad also gambled, drank, and fathered a dozen children. George’s mother, Guillermina, kept the family going. She made a good pot of beans and rice. She made sure her kids wore clean clothes and bathed regularly. She was a devout Christian who believed prayer might keep her children safe.

George and his pal Joe Doreo swam in the Hillsborough River and never once came close to drowning. Wild Florida boys, they waded the river shallows and avoided the fangs of the venomous cottonmouths. They collected bottles they could sell to a collector for a penny each.

They found stone-age arrowheads and played Cowboys and Indians with them.

They played baseball. Two socks, wrapped tightly and waterlogged from a long soak, became the ball.

They sold newspapers. They waved to the milkman. They could walk behind the cart pulled by the fish monger and smell the day’s catch of mullet or pompano. The early morning brought the ice man to their respective homes. First, he’d grab a huge ice block from his cart with tongs. Then he’d carry the block into the house and shove it into, what else? the ice box.

Cattle, chickens and goats roamed the fenceless neighborhood with impunity. All the grownups, even the white-haired abuelas, gambled on Bolita, a numbers game. Men on street corners whistled at the girls, talked tough, and smoked foot-long cigars. George and Joe were too young for cigars, so they smoked dried guava leaves under the porch.

“Oh, they’d make us sick,’’ Joe told me once. “We’d turn green.”.

When Phillips Field opened in 1937 it was as if the Coliseum in Rome had migrated to Roberts City. The University of Tampa played football games at Phillips Field. The University of Florida Gators played an annual game at Phillips Field. All the high schools, black and white, played at Phillips Field. In 1964, Pete Gogolak kicked the first soccer-style field goal in National Football League history for the Buffalo Bills in an exhibition game held at Phillips Field.

As a teen, Joe raced his stock-car at Phillips Field in his Chevy. His Italian immigrant dad, Sam Doreo, cheered him on, possibly because Joe’s car was sponsored by the family business. Like his dad, Joe became a tile and terrazzo man.

One time, Joe told me a favorite story. It was about how he made counterfeit admission tickets for himself and friends to enter Phillips Field for free. The boys often slipped past sharp-eyed guards without trouble, but Joe never forgot the name of the cop who occasionally nabbed them. Manny DeCastro, you old ghost, rest in peace.

Phillips Field, RIP, is a ghost too.

George Lopez had his own special memories. These were the things he thought should be remembered by 21st-century visitors to Julian B. Lane Riverfront Park. Remember the Matassini family and their fish market, George said. Remember the neighborhood barber, Valdez, an incorrigible gossip. Remember that you could buy a good lunch at a fair price at “Happy Tony’s.” Everybody in the neighborhood shopped at groceries owned by families named Conte, Papia, La Cooperativa, Cardinale, Guida, Tomassino, Coqnina, Bernardo. While you squeezed the melons at Bernardo’s, a mechanic in the adjacent garage could fix your car.

Everybody had nicknames. A lightly-complected Cuban pal was known as “Powder Face.”

The famous Cuban bread of Tampa was probably invented at LaPopular Bakery. Tampa Linen employed many Roberts City residents. The Buena Vista Hotel offered luxury as well as an indoor swimming pool and a boxing ring. George’s oldest brother, Antonio, was a well-known Roberts City boxer known as “Half Pint” because of his size. Before his bouts, his mother knelt and prayed.

Half Pint was handsome, a good dancer, enjoyed playing gin rummy and a stiff drink of Lord Calvert. He dressed stylishly and smoked Juan de Fuca cigars. When his boxing career was over he got a job removing dangerous asbestos from buildings. The poisonous fibers in his lungs killed him in 1977.

A ghost.

In 2018, I spent as much time as I could with George and Joe. Honestly, I would have adopted them as honorary dads if only to hear their stories about growing up in Roberts City. One day we all drove to the construction site of Julian B. Lane Riverfront Park for a look see.

As I followed Joe walked to the fence, as George, who needed a cane, came up slowly from behind. Gazing through the fence they admired the new park while mourning what was gone.

“Whooeeeoo!” Joe said. “Whooeeoo! Things change.’’

“You know what?’’ George finally said. “This park, though. It’s going to be nice. I think people are going to love it.”

He imagined the future sunbathers on the lawn, the kayakers on the river, the moms pushing babies in strollers, the teen boys shooting baskets, the dads pitching baseballs to their daughters, the young couples holding hands, the ice-cream cones eaten under the oak canopies. Perhaps some free-tailed bats would flap through the dusk as they did in times long past.

And perhaps 21st century kids would find a place to ride their bikes. When they were boys, George always rode on the handlebars of Joe’s bicycle. Kids. They were going to live forever.

The world may change, but it keeps on turning.

About the Author

Born in 1949, Jeff Klinkenberg grew up in Miami and began exploring the Florida Keys and the Everglades as a small boy. He started working at The Miami News when he was 16 and became a journalism graduate of the University of Florida. Jeff Klinkenberg wrote for the Tampa Bay Times from 1977 to 2014. He is the winner of the Florida Humanities Council 2018 Florida Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing; a two-time winner of the Paul Hansell Distinguished Journalism Award, and a recipient of a 2018 Florida Folk Heritage Award. He is the author of Alligators in B-Flat: Improbable Tales from the Files of Real Florida; and Seasons of Real Florida.